Understanding the in-feed mycotoxin challenge

Published Thursday, 2nd November 2017

The presence of mycotoxins in straights, manufactured feeds and forages has the potential to seriously affect on-farm production.

Yet within much of the industry the threat is still overlooked, says Dr Derek McIlmoyle, AB Vista GB & Ireland Technical Manager - and the role of mycotoxins in reducing cow performance, health and fertility continues to go largely unrecognised.

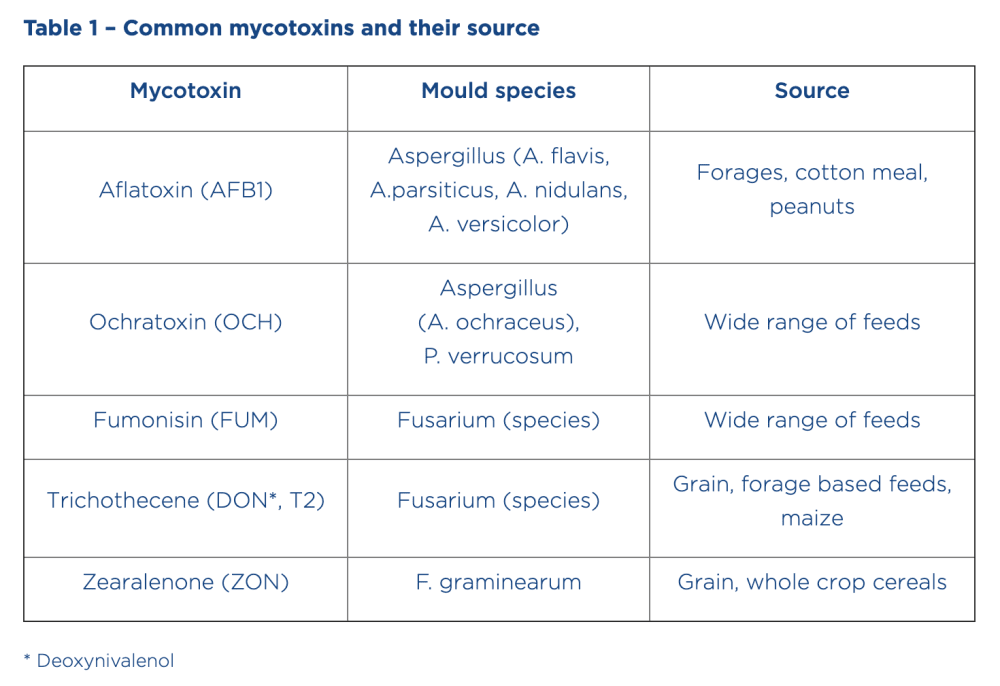

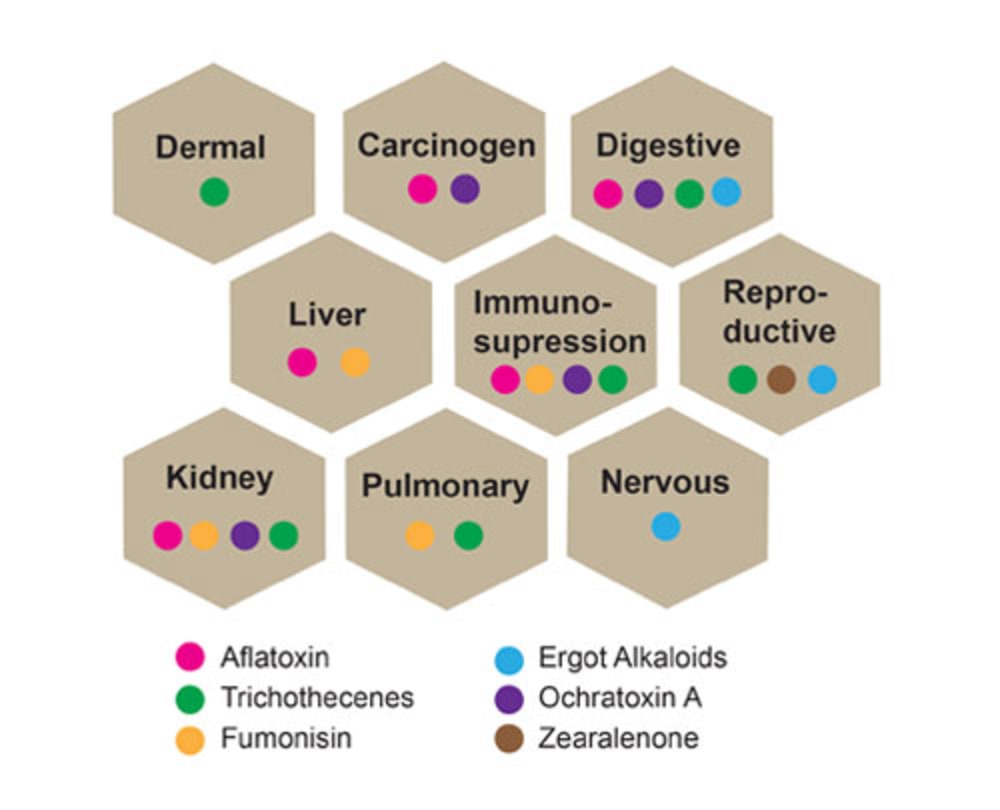

Mycotoxins are produced by a wide variety of moulds and fungi, and whilst there are more than 300 types of mycotoxin, there are five main groups that are of particular agricultural interest (see Table 1). These fungi can invade feedstuffs in the field, during harvest and when being processed – regardless of the country of origin – as well as during transport and storage, with both insect and mechanical damage capable of increasing the extent of fungal colonisation.

Livestock production impact

The ingestion of these mycotoxins by livestock is important because of the potential high level of toxicity even at very low concentrations (parts per billion). The adverse effects are many and varied, and the impact on production livestock can be substantial (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Negative effects of different mycotoxins in production livestock

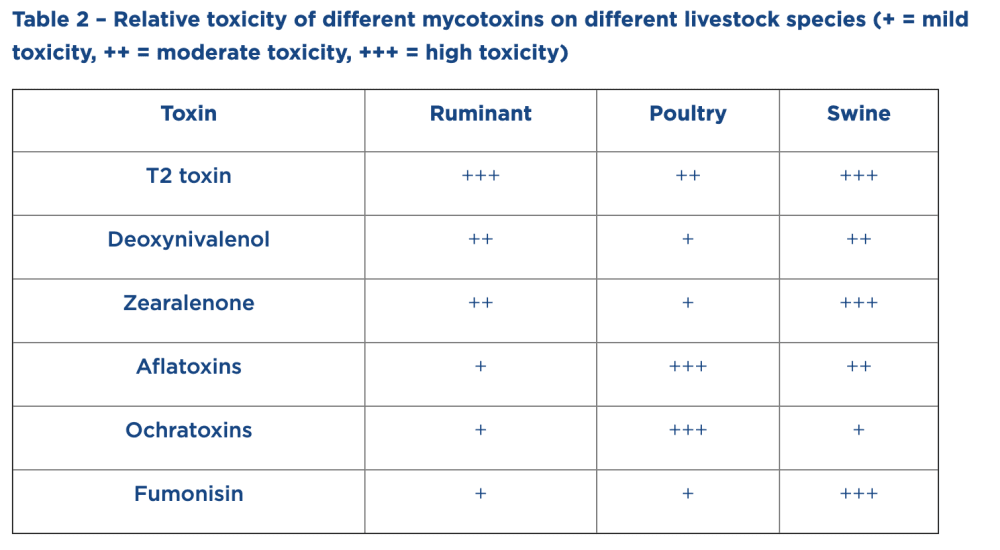

In ruminants, the Fusarium mycotoxins deoxynivalenol (DON), zearalenone (ZON) and T2 toxin are the most toxic, with fumonisin (FUM) and the Aspergillus-produced aflatoxin (AFB1) less so (see Table 2). However, AFB1 is still an important threat, since in-feed contamination (particularly high in cereal grains) can result in aflatoxin M1 (AFM1) in milk. As a human carcinogen, AFM1 levels are closely monitored, and high levels can result in milk being rejected by processors.

There are also anecdotal reports that this transfer of aflatoxin into milk is increased in the presence of other mycotoxins, such as those from Fusarium moulds. This is a good example of the additive or even synergistic levels of toxicity that can result from ruminant rations being contaminated with more than one mycotoxin at a time.

Dairy cows suffering from sub-acute ruminal acidosis (SARA) – a growing challenge as milk yields and ration energy densities have risen in recent years – are at particularly high risk from mycotoxicosis. Specific rumen microbes are able to ingest, transform or degrade mycotoxins and render them less harmful, yet this defence against mycotoxin ingestion is undermined during bouts of SARA.

Differing mycotoxicosis threat

In contrast, AFB1 poses the greatest threat to poultry, being first identified more than 50 years ago following the so-called ‘Turkey X Syndrome’ outbreak in 1960. The ochratoxins (OTA) are also highly toxic, and are associated with renal dysfunction and kidney damage, as well as reportedly affecting weight gain, feed intakes and immune function. Both of these mycotoxins can cause increased mortality in poultry where levels of exposure are high.

However, of the main production livestock species, it is pigs that are the most sensitive to mycotoxin ingestion, with ZON, FUM and T2 toxin posing the greatest risk, and ZON the mycotoxin most commonly implicated in reproductive failure. The threat from AFB1 is also significant, with the same potential transfer to milk as seen in ruminants reported to reduce immune function in piglets.

Feed contamination challenges

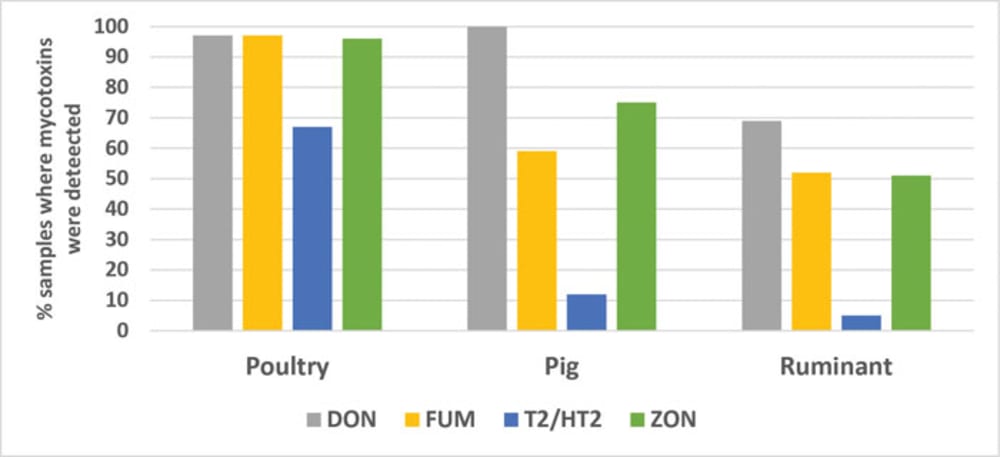

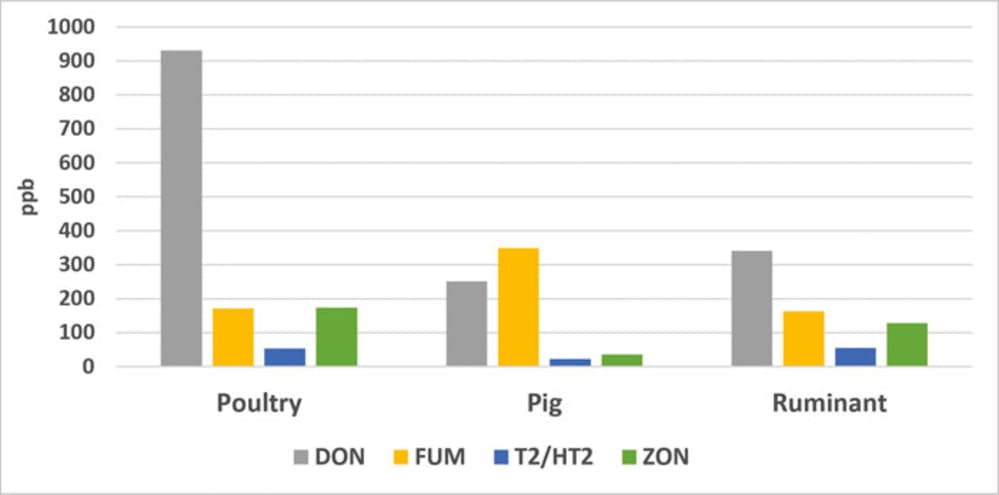

One of the main challenges facing the feed industry is the difference in the mycotoxin load faced by each species. This was highlighted by a study of feed and feed ingredient samples from across Europe, the Middle East and Russia by Micron Bio-Systems (see Figure 2). Although only the Fusarium mycotoxins were detected in this particular study, the results (Figures 2a and 2b) confirm the greater frequency and level of mycotoxin contamination in poultry feeds, for example.

a) Frequency of mycotoxin contamination

b) Level of contamination where mycotoxins detected

Figure 2 – Mycotoxin contamination in tested feed samples by species (Source: Micron Bio-Systems)

However, this doesn’t necessarily imply that the poultry are more exposed to mycotoxins compared to other livestock species, as differences in the volume of feed each consumes also need to be taken into account. Even at a similar total dietary mycotoxin load, such as 2ppm, the mycotoxin intake per kg of bodyweight is much lower for a typical layer (0.01mg/kg) than in mature sows (0.07mg/kg).

It is important to note that manufactured feeds rely heavily on human-edible ingredients, and those batches failing to meet the more stringent mycotoxin limits for human consumption often find their way into animal feed. In addition, many feeds make extensive use of co-products from the human food chain, where processing can concentrate the mycotoxin load.

Moisture risk

Critically, both dry and moist feeds are at risk, with the latter often now used in the manufacture of moist blends for ruminants. The risk to the former comes from mould growth whenever conditions from ripening to feeding are moist or humid – a particular challenge for those crops grown in areas of the world with high humidity – whilst the latter will rapidly develop moulds if stored for extended times without proper clamping and air exclusion.

Particular care therefore needs to be taken to ensure feed storage facilities are capable of keeping feedstuffs dry and free from moisture, whether that moisture comes in the form of high humidity, leaking roofs, yard run-off or contamination from moist feeds. Remember that any feed which is obviously mouldy should not be used for livestock feed production.

If in doubt, it is well worth testing individual feed ingredients or completed feeds or blends using a service like Mycocheck (mycocheck.co.uk), which can quickly confirm whether mycotoxins are a problem. Identifying the type of mycotoxin and its related fungi can also help determine the source.

De-activation supplements

Some of the clearest demonstrations regarding the impact mycotoxin ingestion can have on performance come from research trials involving the addition of commercial mycotoxin binders or de-activators to the ration. For example, a high quality mycotoxin de-activator included in the diet of a high yielding dairy cow can typically produce improvements of 2-3 litres/cow/day where contamination levels are high.

However, de-activator efficacy has recently been shown to be highly species-specific, due to key differences in mycotoxin threat and digestive physiology. This has resulted in growing interest in mycotoxin de-activators targeting the needs of each species. Poultry are likely to be exposed to greater levels of Fusarium mycotoxins, for example, but consume only small volumes of feed and are most susceptible to AFB1 and OTA.

Such differences are already recognised by key regulatory authorities. In the EU, maximum permitted limits for FUM and ZON in pig feed are set at 5ppm and 0.1ppm, respectively, whereas in poultry the limit for FUM is 20ppm and there is no specific limit for ZON.

Species-specific solutions

The recent development of species-specific in-feed mycotoxin solutions therefore represents a major advance. For the first time, ruminant-specific de-activators such as Ultrasorb R are available which have been designed to deliver maximum efficacy at pH6, which is typically found in the rumen, not the pH2-3 of the stomach. Such products are also formulated to target the main mycotoxins of concern in ruminants, such as by ‘opening up’ DON for deactivation in the rumen.

In contrast, equivalent products for pigs and poultry can be formulated to operate in the highly acidic conditions of the stomach and tackle the particular mycotoxin threat faced by each species. As a result, these latest de-activators have not only superseded the basic clay mineral-based mycotoxin binders of the past, but also the older-style de-activators formulated to work across all livestock species.

With a low cost and suitable for inclusion during feed manufacture, in blends or even supplied as part of a mineral and vitamin premix, such de-activators make it possible for many more livestock herds and flocks to be routinely protected against mycotoxin ingestion. With the threat from mycotoxin contamination of feeds unlikely to reduce any time soon, the benefits, in terms of improved livestock health and performance, are likely to be substantial.

Latest news

Stay ahead with the latest news, ideas and events.

Online Feed Fibre Calculator

Calculate the percentage of dietary fibre in your feed

Our calculator is designed for nutritionists and uses averages of global raw materials to calculate the dietary fibre content (plus other more in-depth fibre parameters) of finished animal feed. These parameters are available within AB Vista’s Dietary Fibre analysis service (part of our NIR service).

Sign up for AB Vista news

A regular summary of our key stories sent straight to your inbox.

SUBSCRIBE© AB Vista. All rights reserved 2025

Website T&Cs Privacy & Cookie Policy Terms & Conditions of Sale University IDC policy Speak Up Policy